One of my favorite quotes by Albert Einstein is, “Every problem should be simplified as far as possible, but no further.” The 50/30/20 rule fails his axiom.

United States Senator Elizabeth Warren popularized the 50/30/20 rule in her book, All Your Worth: The Ultimate Lifetime Money Plan. It’s a popular guideline that she calls “a good rule of thumb” and suggests dividing your income into three categories: 50% for needs, 30% for wants, and 20% for savings, all after tax, of course. But is this rule really the best way to manage your finances?

The fact is, people like it because it requires very little thought, and this rule could be a helpful starting point. However, let’s illuminate some of the many blind spots that make the 50/20/30 rule one of our least favorite guideline.

Let’s look at how it works:

First, you allocate 50% of your after-tax income to your needs. These are the things you’d have a really hard time doing without, or the consequences of doing without could be severe:

- Rent or mortgage payments

- Utilities (includes high-speed broadband connection only if it’s crucial to your livelihood)

- Transportation (a car if needed, or public transport if that offers a plausible alternative)

- Health care (insurance premiums, copays, co-insurance, and deductibles)

- Insurance (renters or homeowners, and auto if you drive)

- Minimum debt payments

Next, you allocate 30% to wants. This includes everything that’s not in the “needs” category above, and that doesn’t increase your net worth. Some examples include:

- Eating out and entertainment (movies, shows, etc.)

- Discretionary spending (another pair of shoes, replacing a two-year-old phone that still works fine)

- High-speed broadband connection (except when it’s crucial to your livelihood)

- A car (assuming public transport offers an acceptable, albeit less convenient solution)

- Cable TV and streaming services

- Gym membership

- Amazon Prime membership

- Upgrading to higher-cost alternatives (e.g., buying a new luxury vehicle rather than keeping a reliable vehicle)

Finally, the last 20% goes to savings, which includes:

- Building up an emergency fund of at least three months’ needs, and preferably more

- Paying down high-interest debt as quickly as possible

- Contributing to an employer’s retirement plan – enough to capture all of the employer match

- Contributing to an IRA, HSA, and/or other tax-advantaged plans

- Investing in a taxable account for goals closer than retirement

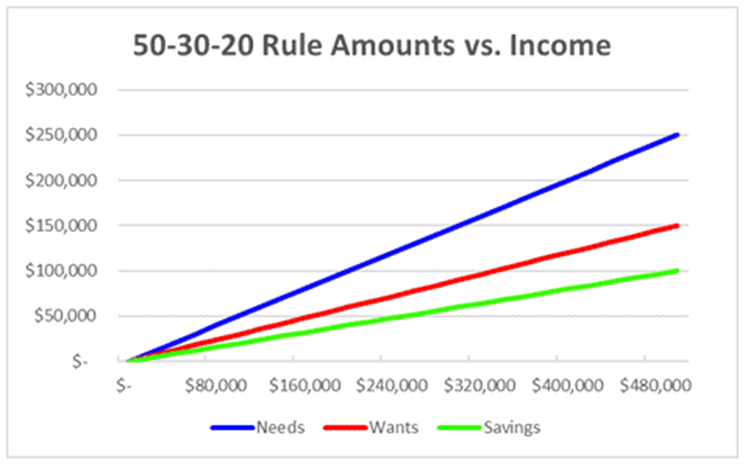

Sounds good, right? Here’s a visual to help you see why we call this budgeting tool a huge mistake. You can see for lower household incomes, 50% of your income may not be enough to cover basic needs. Yet, the more you earn, the savings component may have you coming up short at retirement.

A major issue with the 50/30/20 rule is that it fails to account for individual circumstances. Everyone’s financial situation is different. Debt, housing costs, and income help make up one’s financial footprint, and just like a pair of shoes, one size doesn’t fit all. Also similar to a pair of shoes, consumers often get confused with NEEDS vs. WANTS. Or as we say here at OmniStar, REQUIRED vs. DESIRED.

Example: Buying an expensive piece of art to decorate your home is pretty clearly a want, not a need. Paying excessive rent, on the other hand, can easily be confused, even justified.

Elizabeth Warren’s “good rule of thumb” fails in many more ways. What if your after-tax income is $40,000? Chances are you don’t have any money for savings or wants. Alternatively, what if you are making $200,000 per year after tax? How much sense does it make to spend 80% on needs and wants?

The higher your income, the more you must save for retirement or risk a huge lifestyle shift when your income stops. This is precisely why “one size fits all” doesn’t work. Moreover, you won’t have enough on hand in the event of unforeseen circumstances.

Then there is the weakness of failing to consider the importance of debt repayment. If you have high-interest debt, such as credit card balances, prioritizing lifestyle over debt repayment and savings will cost you more in the long run. The rule is 20% goes toward savings and debt repayment. Here’s the problem. The rule doesn’t consider how much it might take to build your emergency savings, pay-off debt, maybe save for children’s education, and adequately fund your retirement.

Instead of blindly following this archaic rule that seems to be as hearty as a cockroach, consider customizing a budget that aligns with your specific needs and priorities. I encourage you to find an advisor who can help you create a plan that is best for you.

Remember, budgeting is not about restricting yourself but about making informed choices that support your financial well-being. It’s about freedom. Your financial house is your own, so don’t try to use a rule that wasn’t designed for you.